At the recent International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) meeting on biodiversity in Hawaii last September I was asked by one of my good friends, Azzedine Downes, who happens to be President of International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) if I would give a short talk at a gathering they were organizing – about pangolins! Azzedine knows I cannot refuse him and so of course, I had to say “yes!” The purpose of the evening was to help persuade countries around the world that all pangolins should receive the highest level of protections from international trade.

I remembered the first time I heard about them from Louis Leakey in 1957. It was that magical year when he invited me to join his tiny team at Olduvai Gorge – a couple of years before the first hominid remains (Zinjanthropus) were found there. He described these strange creatures that look a bit like anteaters or armadillos, but are covered in scales. When threatened, a pangolin rolls up in a ball like a hedgehog. Sometimes it lashes out with its tail – the scales on which can easily cut a predator’s skin. As a final deterrent these curious creatures can emit a noxious-smelling acid from glands near the anus, similar to that of a skunk (although they do not spray the liquid).

Leakey also told me that he once saw a pride of lions surrounding a ‘pangolin ball,’ patting it with their paws, pouncing on it and biting at it. After some time they gave up and walked away – the unharmed pangolin then unrolled itself and hastened off in the opposite direction. There are a number of similar stories on YouTube today.

Pangolins really are strange creatures. They have their very own Order, Family, and Genus that originated some 80 million years ago. There are eight species, four found in Asia (Chinese, Sunda, Philippine, and Indian) and the other four in Africa. The one I might have met on the Serengeti is the giant ground pangolin, also found in forested areas including Rwanda and Burundi, and Western Tanzania (Mahale National Park and almost certainly also in Gombe). Dr. Anthony Collins has twice encountered a pangolin – either a giant ground or a ground pangolin on the beach at night. He took this wonderful photograph.

At Gombe, I think we also have the tree pangolin. Back in 1970’s, I was up in the forest when I heard a group of chimpanzees giving the alarm call “wraaaah” – a savage, spine chilling sound. I hurried as fast as I could to see what was going on, and found a group of three adult males and a few females some way up a low tree. They all had fully erect hair and were staring down and screaming at something in a hole in the tree. By climbing up a nearby tree I was able to see a pangolin who had obviously taken refuge there. Only the scaly back was visible. One chimp got a stick and poked at the poor animal – but the scales provided excellent protection and eventually the chimpanzees lost interest and wandered off. I waited a while, but it was getting late and I left without seeing the pangolin again.

It is not surprising the chimps were a bit scared of such a strange creature for I don’t suppose they see one very often since pangolins are nocturnal and solitary for the most part. (Only the long-tailed pangolin of Central and West Africa, I am told, is regularly active during the daytime). There are no pair bonds between male and female: the larger male marks his territory with urine to attract females but then, after becoming pregnant, she wanders off on her own until giving birth to her one pup. For three months this infant will ride around on her tail – how I long to see this – and then will stay with her for a few more months, during which I suppose it learns the pangolin way of life, how to locate termite mounds (mostly by smell as they have bad eyesight). Eventually the youngster feels confident enough to leave mum and start its independent life

(AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

With a pilot camera trap program in Gombe we can see some of these behaviors. See how they scratch open a termite or ant nest and thrust their long (longer than their bodies!) and sticky tongues down the passages to collect the insects. They have no teeth for chewing, but the insects are ground up by keratinous spines inside their stomachs. They really are strange creatures! Elizabeth Lonsdorf, one of our researchers working in Gombe has captured some great footage of a pangolin feeding.

The pangolin is the most illegally traded mammal in the world, hunted for meat and for the supposed medicinal value of their scales. IFAW put out information that an estimated one million pangolins were poached from the wild in the past decade to satisfy the demand from consumer countries including China, Vietnam – and the United States. As pangolin populations dropped in consumer countries, dealers began to seek pangolins in other places including Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent and now Africa.

Although the scales are simply keratin, and have no medicinal value, in traditional Chinese medicine they are dried, roasted and sold. Some believe they can cure just about everything from cancer to acne, though there is no evidence to back this idea. In Africa too, pangolin scales are valued in some places: when a researcher at Gombe found a dead pangolin, the park ranger who was with him asked if he could have one of the scales. He believed that if you burned the edge of the scale with a match the smoke would keep lions away. (Even though there have been no lions at Gombe for over 50 years!)

Because of all this false belief in their value, pangolin scales can sell on the black market for over $3,000USD a kilogram. Pangolins and/or their scales are smuggled back to consumer countries via large shipping containers, often containing several tons of pangolin scales and frozen meat. People are surprised to hear that the United States is a consumer country – but U.S. government data shows that over the last decade, over 26,000 products made with pangolin derivatives were seized by the federal government on their way into the U.S.

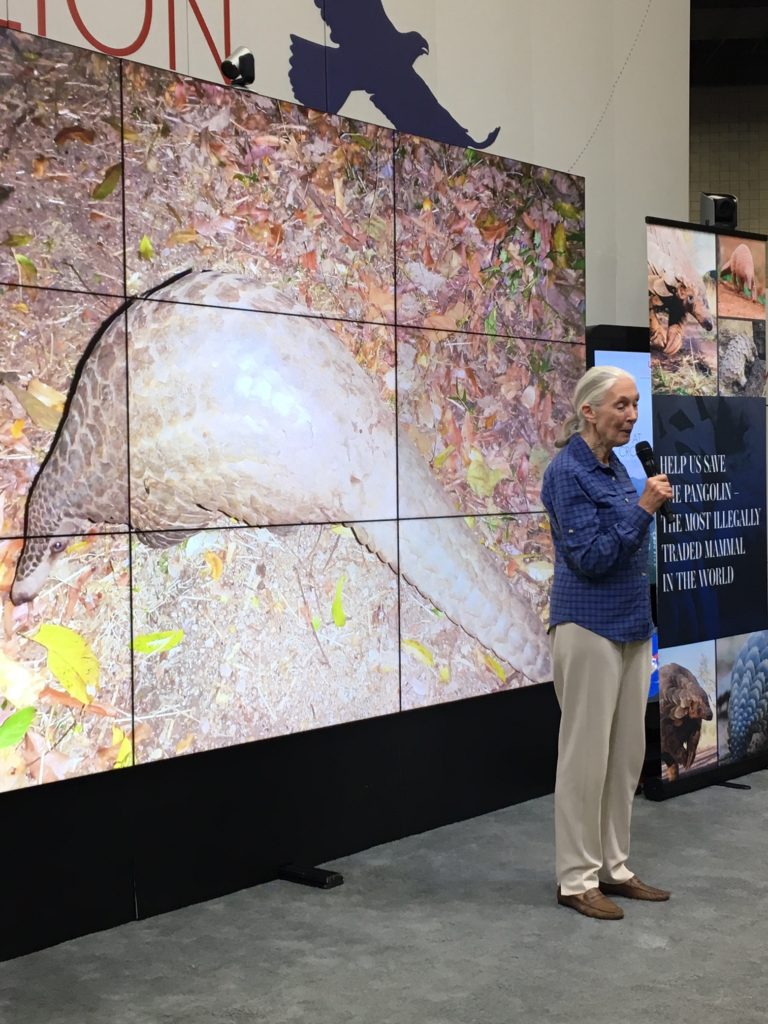

It is estimated that 100,000 pangolins are captured every year from across Africa and Asia, with most shipped to China and Vietnam. This illegal trade has now rendered pangolins the most trafficked animal on earth, with some estimates claiming that sales now account for up to 20 percent of the entire wildlife black market. In September, I gave my talk at the IUCN meeting, alongside Azzedine, and also IFAW North America Director , Jeffrey Flocken and pangolin experts Lisa Hywood, Thai Van Nguyen, Darren Pieterson, and Dan Challender.

After that meeting the countries of the world gathered in Johannesburg, South Africa, at the CITES Conference, and voted to transfer all eight species of pangolin from Appendix II to Appendix I! This means that pangolins will receive the strictest global protections from trade possible. Thus, whilst it is horrifying to think that all species are so endangered, we must hope that the new level of protection will save these wonderful animals from extinction before it is too late.

And, to end on a note of hope, the Carnivore and Pangolin Conservation Program (CPCP), a collaboration between Save Vietnam’s Wildlife (SVW) and Cuc Phuong National Park, released 20 Sunda Pangolins last August to a safe and undisclosed location in Vietnam. The critically endangered pangolins were rescued from the wildlife trade and rehabilitated at SVW/CPCP in Cuc Phuong National Park, Ninh Binh Province.

The released pangolins were part of a seizure of 22 live pangolins confiscated by the Forest Protection Department (FPD) officers in Ninh Binh Province in June 2016. Pangolins normally do not survive well in captivity, and yet of the 21 pangolins confiscated, 20 survived and were released. Phuong Quan Tran, Manager of the CPCP, said, “This successful release and high survival rate of the rehabilitated pangolins is in large part thanks to the cooperation of Ninh Binh FPD which enabled us to release the animals quickly and avoid the high mortality that pangolins normally experience due to captive stress.”

Sometimes people forget that each animal, once you get to know it, has its own personality. Becci and Mark Crowe, two of our supporters (of the Jane Goodall Institute in USA) recently went on a trip to Mozambique. Becci wrote that one of the highlights for them was having the opportunity to spend time with a juvenile pangolin named Pea who had been confiscated from poachers. Pangolins are nocturnal, and every night Pea was taken out into the bush so that he could learn how to search for ants and termites, and the Crowe’s got to join him on these walks. Becci fell in love with the strange animal and told me that he was the most gentle and vulnerable little soul. Recently we got the wonderful news that Pea, having learned the skills necessary for survival, had been released into the wild. I am hopeful that he will survive and am hopeful that this beautiful and fascinating species will live on, as we all work together to protect it.

Update*

Social media posts about endangered pangolin being eaten at banquets have caused Chinese authorities to launch an investigation with those caught eating potentially jailed for up to 10 years. (BBC) One wildlife protection specialist saw a ray of hope. “I hope the scandal will become a turning point in our search and rescue of the critically endangered animal,” said Zhou Canying, head of the Wildlife Protection Association in Changsha, Hunan province. With this increased exposure of the continued threats to pangolin, the Chinese people and people internationally are calling for more intense round up of trafficking ring leaders and others in the demand and supply chain for the pangolin. With some luck, this may be part of the many interventions to help protect this most trafficked animal.