It was a sad day for conservation and for his many collaborators, friends and especially his family, when John Hare left Planet Earth on February, 2nd, 2022. John was one of my great friends – and I use ‘great’ in its truest sense for he was one of the great adventurers and explorers, always ready to take on new challenges, travelling into some of the wildest, most inhospitable places in the world, facing with courage – and subsequently described with a British sense of humour – the many dangers he encountered. He didn’t look like a tough guy, burley and rugged, but his slim elegance concealed an incredible power of determination and endurance. There will never be another John Hare.

I first met this remarkable man in 1997, just before the publication of his first book about wild camels and when he was in the process of establishing, together with the international environmental lawyer and conservationist, Kathryn (Kate) Rae, the UK charitable foundation, the Wild Camel Protection Foundation (WCPF). He was also working with Chinese scientists to persuade the Chinese government to establish the 67,500 sq mile Lop Nur Wild Camel National Nature Reserve. I was really excited to hear about these wild camels and we talked for ages. He was trying to raise funds for 5 ranger posts in this vast reserve (almost the size of Texas) and I was able to persuade two of my generous friends to provide the money for 3 of them (Fred Matser and Robert Schad).

John told me how his fascination with the Wild Camel began. In 1992, he was in Moscow to organise an exhibition of environmental photos. On the opening night there was a reception where he met the Russian scientist Prof Peter Gunin. The two got talking, and Gunin told John he was getting ready for his annual expedition into the the harsh environment of the remote Mongolian Gobi desert to survey the wildlife there. The adventurous spirit in John was at once stirred – and he asked if a foreigner could join the expedition. Gunin asked if John was a scientist. Unfortunately, not – “but I could take photos” he said. However, they had a photographer. “Do you use camels on your expeditions?” asked John, explaining how he had worded with camels when he was with the British foreign service in different remote areas of Africa. Gunin’s face lit up. Yes, they needed someone to undertake a survey of the wild camel population in the Mongolian Gobi. John was accepted - provided he could get the $1,500 foreign exchange they needed and pay his airfare. And so John was taken on to join the Joint Russian Mongolian Scientific Expedition as a wild camel expert.

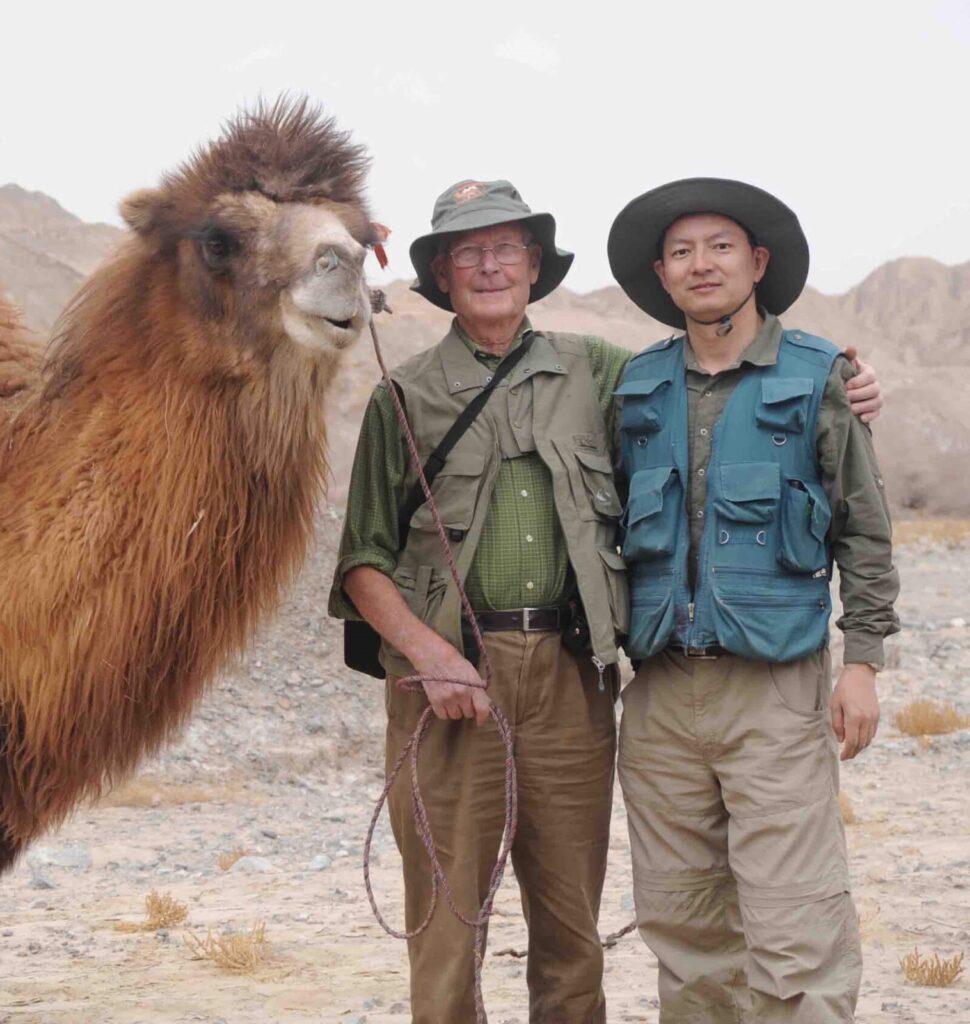

Dr. Yuan Lei is the son of Professor Yuan Guoying who accompanied John Hare on all his Chinese expeditions. Yuan Lei is now the Director of the Reserve (WCPF)

That expedition changed his life. He subsequently helped to organize four expeditions (in 1993, 1995, 1996 and 1997), two using domestic Bactrian camels, into the Lop Nur and Gobi deserts in China and Mongolia to discover the range of the wild camel, (three fragmented populations in China and one in Mongolia). It was perfect, for he was able to combine his passion for adventure with a desperately needed conservation program. For the rest of his life John worked with Chinese and Mongolian scientists, government officials, and the local people to protect the few remaining wild camels, now found only in China and Mongolia.

The Lop Nur Desert is the largest saltwater desert in the world and because it is where China has carried out underground nuclear tests, it was closed to visitors for 45 years. The camels living there apparently survived this radiation and continued to breed. John Hare was the first person to receive official permission to enter the area. Subsequently, he made a number of journeys with his Chinese and Mongolian colleagues into the Lop Nur and Gobi deserts, mostly with domestic Bactrian camels, to map out the extent of the range of the Wild Camel.

During these trips they entered many previously unexplored and unmapped areas and often found themselves in somewhat desperate situations. My favorite story of the many he shared with me took place in Lop Nur. He was with an old friend from their time together, working with camels, in the foreign service in Africa, and there were 5 or 6 Chinese camel handlers. A sudden turbulent sand storm caught them unaware. Their 20 camels ran off, carrying most of their supplies. The small group was in a desperate situation for the sand storm had obliterated the tracks of the camels so that they didn’t even know in what direction they had gone. After much discussion, 2 of the Chinese companions, with a few of the supplies that they had managed to unload, set off walking in the direction they thought the camels had gone. The others just sat there and waited. Their only food was the grain fed to the camels, and a limited amount of water. After three days the situation was grim. John’s friend felt that John and the Chinese colleagues should set off walking. He was lame and would be unable to undertake such a trek. So he asked John to do the “decent thing, old man” and handed him his revolver. “I just laughed”, John told me – he was not about to shoot his old friend – They would face the end together. They waited. Suddenly the oldest of the Chinese companions said something to the other two who at once became very excited. They stared at the sky. “Yes, I see them, I see them” they cried. At first John could see nothing but then – there they were. Three swallows – symbols for new beginnings in China. But why were they there? 2,000 miles away from any migration route? The birds came close, circled round the small group of men, touched each one with the tip of a wing - and vanished. The Chinese men who had been tense and nervous, relaxed. And within a short time the runaway camels were seen returning, led by their handlers. The little expedition was saved.

With his colleagues John was able to obtain a historic agreement, with governments on both sides of the Mongolian/Chinese border to protect the wild camels in their countries, and share information. On his land in England John set up a ger – the Mongolian equivalent of a Russian yurt – and he invited two young students, one Chinese, the other Mongolian, to spend two days with him. Whisky flowed, stories were told, and songs sung. Friendship was forged and deepened and this, eventually, resulted in more collaboration between the camel researchers of the two countries. “Technology is wonderful,” John said to me once, “but nothing compares with good human contact.”

When he began this work it was thought that these two-humped camels were the same species as the domestic two humped Bactrian camel but genetic testing subsequently revealed that they were a separate species – The Wild Camel, whose ability to survive in the harshest of conditions is almost unbelievable. They can, for example, drink water that is several times more salty than the sea.

In spite of all efforts to protect the remaining wild camels, they still face many threats. And so, as a safeguard against their extinction, in 2003 the WCPF established in Mongolia the only captive wild camel breeding programme in the world. This programme has been successful, but the current 60 hectare site has reached capacity with 35 wild camels (young and old). Some camels have been successfully reintroduced into the wild, but even so it is desperately necessary to establish a second site. The local government in the area has approved the plan for a second breeding centre - and WCPF is now engaged in an urgent fund-raising campaign to make this a reality.

As I know only too well, the fight to secure sufficient funding for conservation efforts is never ending. In order to raise awareness, and money for the WCPF, John organized and participated in several expeditions with domestic camels that proved that the passing of years had done nothing to subdue his love of exploration and adventure. In 2006 he successfully, and for the first recorded time, travelled around the circumference of Lake Turkana (which used to be Lake Rudolph) in Kenya. This expedition involved persuading 22 camels to swim across the mighty crocodile infested, River Omo in Ethiopia, dealing with warring AK47 toting Turkana and Gabbra tribesmen, surviving temperatures of up to 60 degrees Celsius and crossing brittle and brutal lava flows.

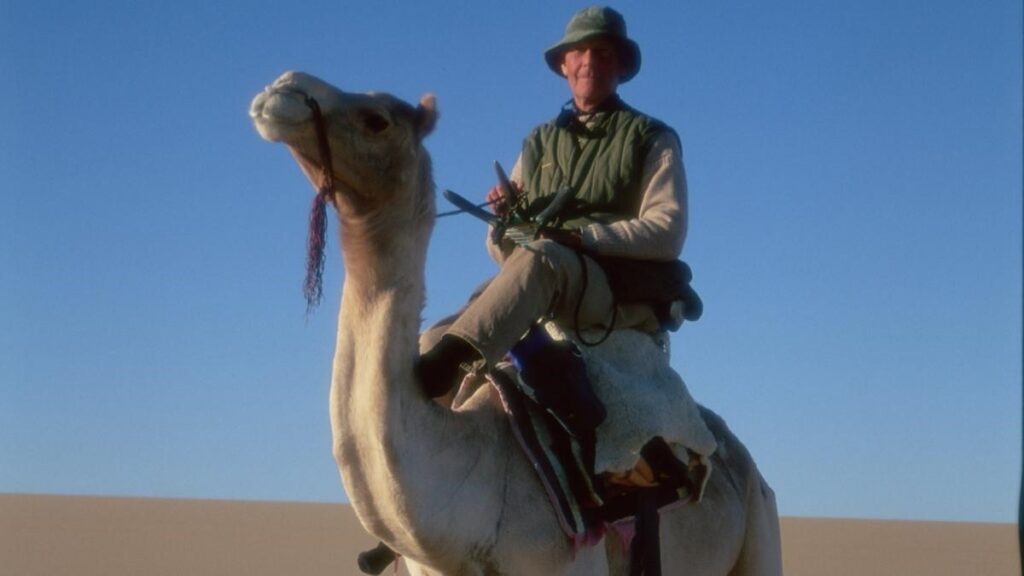

Then, in 2001/2002 John crossed the Sahara desert along a former ancient camel route from Lake Chad to Tripoli, a journey of 1,462 miles. He travelled with four Tuaregs, a Chinese professor, a white Kenyan rancher, a young Englishman and 25 Dromedary (one humped) camels. During this gruelling journey that lasted three and a half months, John rode a camel called Pasha and by the end, he told me, she followed him round like a dog, sniffing at his pockets hoping for some of her beloved dried dates.

John together with Kate and their team of supporters also raised money by putting on imaginative events in the UK. Lady Chichester, a patron of WCPF, owns two domestic Bactrian cames, Therese and Temujin. She was the source and inspiration of the Golden Journey, a dramatized history of the Silk Road. This was presented in front of a full house at the Royal Opera House in London. Right at the end, and stealing the show, John Hare appeared on stage, riding as he put it, “a tarted up and sweet smelling Therese.” Temujin was led onto the stage behind them.

Since 2012 the Countess has brought her two domestic Bactrian camels to the U.K. Wild Camel Day to give an exhibition of dressage with camels. These Wild Camel Days are always attended by the Mongolian Ambassador to the U.K. A fundraising event for the wild camels, there are camel rides, Mongolian wrestling, archery falconry displays, Mongolian food and other fun events.

Then there is ‘War Camel,” which was created by the maker of War Horse. War Camel, named Gobi, with his two puppeteers, made a variety of appearances in support of the WCPF. Once Gobi attended a lecture given by John in the Royal Geographical Society in London, standing patiently on the stage as he spoke about the plight of the Wild Camel. Gobi made various visits to raise awareness about the plight of the Wild Camel. Once he visited a Waitrose supermarket – unannounced. Customers and staff were amazed. After walking carefully between the aisles, the team realized they would have to go out backwards, and they – as well as the manager! – were terrified they would knock over a pyramid of wine bottles, (They didn’t!).

I was able to speak with John just a few days before he died. We discussed various things about camels and he asked if I would continue to be a patron of WCPF when he was no longer with us. He was quite calm about his approaching death, facing the unknown, as he had all his life, with courage. He told me his camel was all harnessed up and ready to go. He was quite keen to find out what lay ahead – he and I shared a conviction that the death of our physical bodies is not the end. Two days later Kate told me he had set off on that last adventure.

I like to imagine his indomitable spirit riding his beloved camel Pasha into the unknown and welcomed by a little group of swallows, softly brushing his face with their wings.

No matter what, his spirit will live on. Over the years, hundreds of Wild Camels will live because of his work on Planet Earth. And all of us who knew him, all who admired his achievements, will work to ensure that the organization he created along with Kate ( www.wildcamels.com)will continue to carry out its vital work.