When I heard that Robert had left us, I found it hard to believe. For it marks the passing of an era, the era of the first great early ethologists, Konrad Lorenz, Karl von Fritz, Niko Tinbergen, Robert’s supervisor, David Lack – and Robert Hinde himself.

It is not my intention to write about the huge influence Robert’s work had on ethology, psychology and other branches of science: only on the way he impacted my own career, and the development of the Gombe Stream Research Centre.

When, in 1962, Louis Leakey secured me a place in Cambridge University to work for a PhD in ethology I had not been to college. I had been collecting information about chimpanzee behaviour at the invitation of Dr. Louis Leakey. Nothing was known about them in the wild, no one told me how I should set about this research. And so as I arrived in Gombe with no formal training in scientific methodology I set about my task intuitively. I had to gain the chimpanzee’s trust, identify them as individuals, and write down all that I observed. At first they ran away as soon as they saw this strange white ape, but gradually they realized I was harmless and I could get closer and closer. My equipment consisted of a notebook and a pair of second hand binoculars.

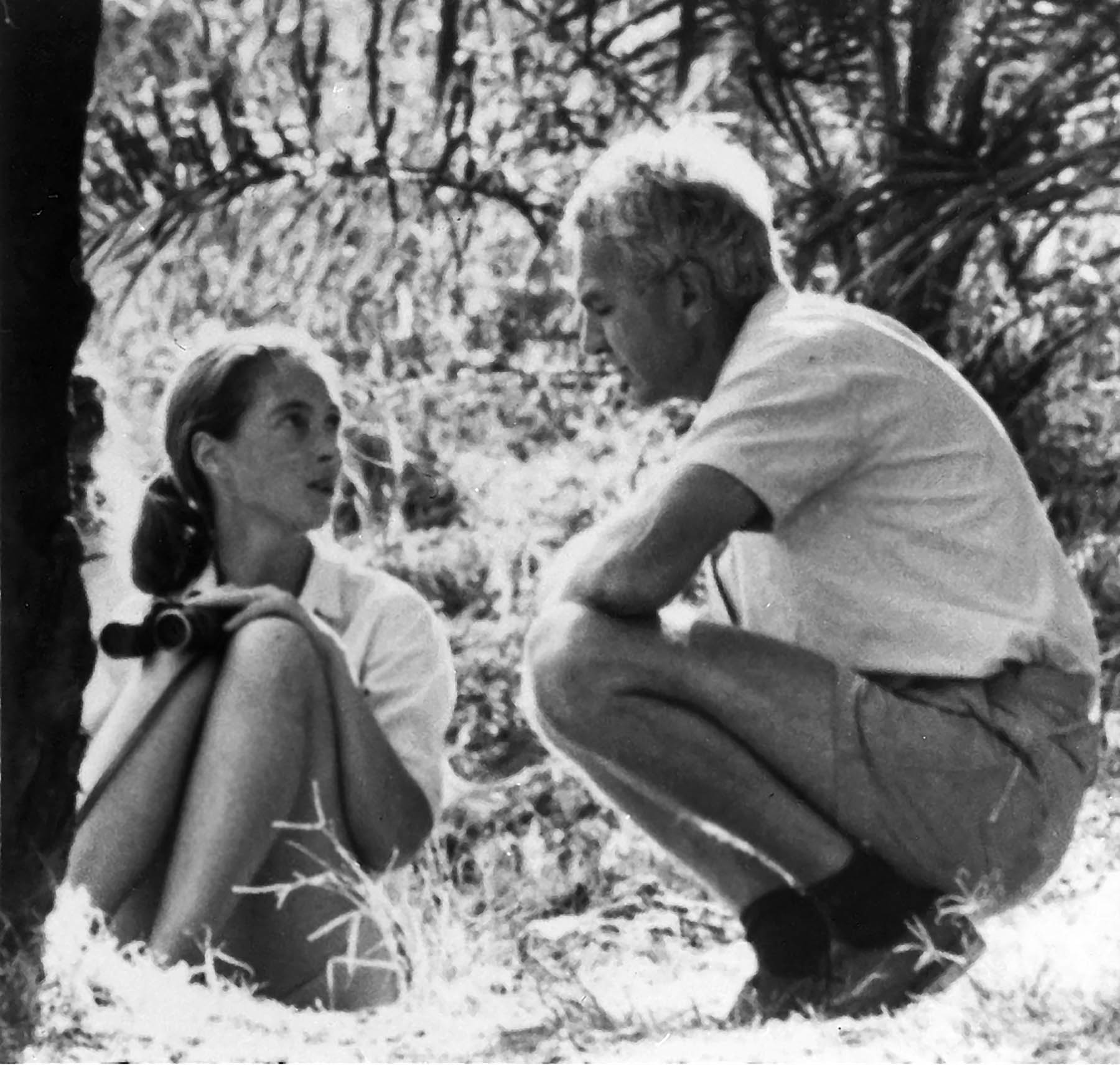

Jane Goodall and Robert Hinde in Gombe Stream Chimpanzee Reserve

I had been in the field for about a year when I received a letter from Leakey informing me that he had secured me a place in Cambridge University to work for a PhD in “ethology” (I had no idea what that meant!). There was no time, he informed me for me to “mess with a BA”.

I was understandably nervous when I first arrived in Cambridge. I soon learned that my supervisor would be Professor Robert Hinde. Because although his main work had been with birds, he had recently established a colony of rhesus macaques at the Madingley Field Station. How fortunate for me!

British ethology was based on cold, hard, objective scientific fact. Most of the professors at Cambridge were shocked that I had named the chimpanzees, rather than assigned them numbers so it was luck for me that Robert’s monkeys were all named.

But he was a stern critic when it come to discussing personality, minds capable of thinking and, especially, emotions in the chimpanzees. I was guilty of the cardinal ethological sin – anthropomorphism. Fortunately my childhood teacher, my dog Rusty, had made it clear that the ethologists, at least in this regard, were wrong. Even more fortunately, Robert Hinde visited Gombe so that he could see my research subjects for himself. He wrote to me, afterwards, that he learned more in those two weeks than in all his previous work with animals.

He was the perfect supervisor for me, and I can never pay sufficient tribute to him for how he helped transform an enthusiastic but naïve young woman into a successful PhD candidate. And, most importantly of all, he taught me to think critically.

Poor Robert! I would write enthusiastically about various aspects of chimp behaviour, struggling to fit my observations into something like the format expected of a “proper” scientist. I would go to visit him at his rooms in St. John’s, feeling not a little proud of a chapter on, for example, infant development that I had handed to him a few days before. As he discussed my efforts, I felt more and more horrified – all my carefully typed pages were liberally covered with criticisms, in red ink. Carefully he explained where I was not thinking like a scientist. I would get back to my digs and hurl the pages into a corner of the room, angry and hurt and, yes, defiant.

But in the morning, after sleeping on it, I would pick up the pages. Read his comments carefully, and realize his reasons for the defilement of my work. But I did not always agree with him, and thanks to my lessons from Rusty, my life long observation of animals, my understanding of chimp behaviour that was getting ever more sound, I was able to stand up to Robert over certain issues. I learned, later, that many of his students were reduced to tears – but he and I developed a really meaningful relationship : he helped me write about my observations and conclusions in such a way that I would be less vulnerable to criticism from more rigidly formal ethologists.

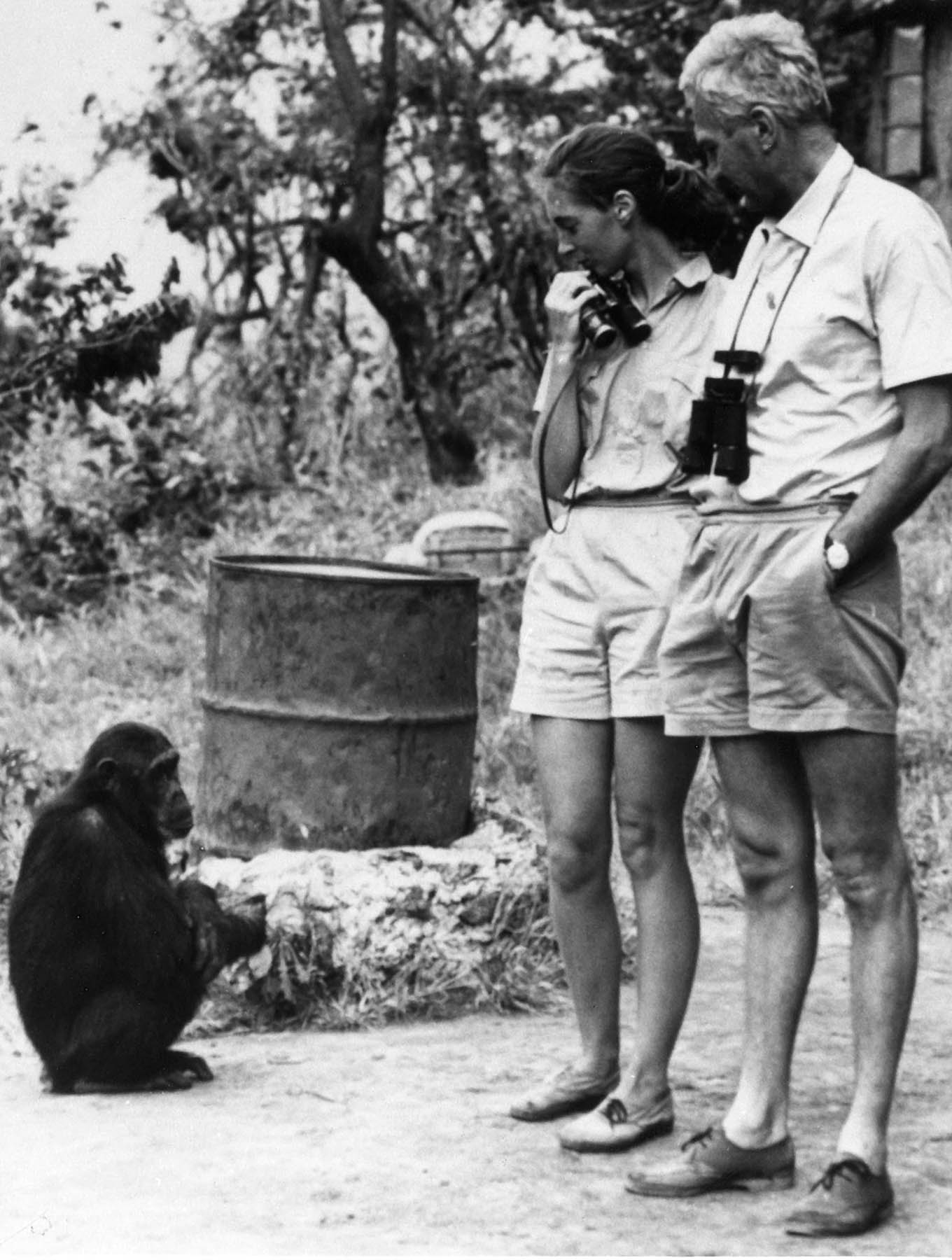

Melissa, Jane Goodall and Robert Hinde in Gombe Stream Wildlife Preserve

One comment was especially useful. In my naïve way I wrote that, after the birth of her infant sibling, Flint, juvenile Fifi became very jealous if other youngsters tried to interact with him. Robert’s comment – “Jane, you cannot say Fifi was ‘jealous’ because you cannot prove it”

I conceded the point. But then, as she clearly WAS jealous, how should I convey this? “Well” said Robert, after careful consideration, “I suggest you say that Fifi behaved in such a way that if she had been a human child we would say she was jealous”.

That wise comment got me through so many difficult moments. And I have shared it with students around the world that they too may benefit from Robert’s common sense.

Even more importantly, Robert helped to design check sheets for use by students and field staff at Gombe that would make the data collection more reliable and easier to quantify. He helped me and the other students understand the importance of time sampling. But at the same time he learned that methods of data recording that were successful for captive studies, did not necessarily work in the wild. He arrived in Gombe with the idea of collecting data in a way that would make it easy to computerize. The students remonstrated with him, explaining that carrying a little box around and punching the keys to make holes in cards could not possibly work in the field. Eventually Robert decided he would try it out himself. One of the students, Geza Teleki, describes how Robert returned from the field: “I can close my eyes and see him walking into camp. He looked like hell. I mean, he was torn up by thorns. He was bleeding from head to toe. His clothes were torn.”

Thus was Robert introduced to the realities of recording in the terrain that the chimpanzees called home! But nevertheless, his visit did lead to a new and more precise way or recording that would allow time sampling: observations were spoken into a tape recorder and the student carried a little beeper that went off every one minute or half minute. The observations could afterwards be transferred onto specially designed check sheets.

Robert Hinde, Jane Goodall, and Flo in Gombe Stream Wildlife Preserve.

Robert’s visit was beneficial in another way – he made applications for funding of the Gombe research from the Science Research Council. This provided much needed stability for three years, during which a number of students worked for their degrees under his supervision at Cambridge University.

He had a huge influence on my career, and he certainly helped Gombe to become a world class field research station – now in its 56th year. I am only sad that, during the latter part of his life, our paths did not cross very often. I still remember our last conversation, at a dinner in Cambridge. We discussed the impact that the Gombe chimpanzees have had on the careers of so many primatologists and, indeed, many branches of science.

Thank you, Robert. I am forever in your debt.

More Reflections From Those Who Knew and Admired Robert:

Anne Pusey

Director the Jane Goodall Institute Research Center, Duke University

I would like to add to this tribute to Robert Hinde. I first met him when I visited Cambridge after spending a year at Gombe, working as an assistant on the mother-infant study. I knew of him as a towering figure in ethology having studied his textbook while an undergraduate at Oxford. Although a busy professor, he took time to show a shy but eager young student the monkeys at Madingley and to discuss how to address the difficulties of data collection under the much different conditions at Gombe.

I stayed in touch as I returned to Gombe to continue as an assistant and later as a Ph.D student at Stanford. Then, in my final year, when my advisor David Hamburg left Stanford to become head of the Institute of Medicine, Robert kindly welcomed me to Madingley to finish writing my thesis. It was an enormously exciting intellectual environment, and many of the writers of the tributes above were there. I still have the manuscript of the first chapter that I submitted to Robert, liberally annotated with numbers corresponding to the numbers on several handwritten pages of his penetrating and sometimes devastating comments, the last remarking that my punctuation was atrocious. But he prefaced these with encouraging and positive words, something that I have tried to emulate with my own students ever since. Later his letters of recommendation undoubtedly opened the doors to my future career.

As Jane describes, Robert had a major influence on developing systematic methods of data collection at Gombe which survive to this day. He was very supportive of initial efforts at Cambridge and Stanford to computerize the data, and later he supported me in our renewed efforts to digitize the data at the University of Minnesota in the 1990s. Now we have more than 40 years of daily follow data in a database as well as a database of 40 years of mother-infant data, thanks to the efforts of Elizabeth Lonsdorf and Carson Murray. These are enabling us to validate patterns of behavior first described by Jane and to examine many questions about long-term maternal influences, personality, social relationships, aggression and intergroup hostility, guided by the framework developed by Robert in the 1970s. I feel incredibly fortunate to be part of Jane’s Gombe family and through Jane to have come under the influence of this great scientist and wonderful man.

Richard Wrangham

“The news of Robert Hinde’s death is deeply saddening.

The great fortune of having been formally mentored by Robert Hinde can be summarized in the observation that his intellectual and moral passions were equally impeccable. And if that sounds an intimidating combination, which of course it was, there was a deeply caring emotion that was ready to step in if a student trembled.

I met Robert when he visited Gombe in 1971. He was Jane Goodall’s mentor and in many ways the intellectual leader of Britiish ethology thanks in part to his 1966 book Animal Behaviour: A Synthesis of Ethology and Comparative Psychology. I was a research assistant studying sibling relationships in chimpanzees as part of Jane Goodall’s projects, and trying to get enough experience to be accepted to graduate school. To my amazement he agreed to try to get me into Cambridge. Much later, when he retired and shared his files, I saw how many letters he had to write to help me in. He did not normally seem much of a gambler, but he gambled then and was far more supportive than I deserved.

For 2-3 decades after I left Cambridge Robert challenged me over the idea that human war and chimpanzee intergroup aggression were biologically related. He drew attention to the many differences of the two systems, and stressed how politically sensitive the topic was. The loss of his elder brother during the second World War was only one of many reasons why he hated war, but he was too good a scholar to dismiss the issues out of hand. Our interactions became very constructive in the last decade. I saw him almost every summer, still feeling some student nerves as I knocked at the door of his rooms in St. Johns, and he still sprinkling a generous number of comments on my manuscripts. It was a joy to find his mind as sharp and concerned as ever up to his final year. In the end we were clearly reconciled on the war issue, to the point where he lightly reprimanded me for writing a book about cooking because it was not an important topic. He had said that he regretted his early work on chaffinch song for the same reason: it was unlikely to help anyone. That was what he wanted to do: he wanted to help people. Perhaps he did not realize how much he had succeeded in doing so.”

Bill McGrew

Hon. Prof., School of Psychology and Neuroscience, Univ. of St. Andrews.

“Sad news. He’s been a part of so many lives in ethology over whole careers, in my case since undergraduate student days in Oklahoma (1960s). I have particular reason to be grateful to him: I met him for the first time at my DPhil viva, where he was the external examiner (1970). Daunting! But, as ever, he was firm but fair. He reviewed my first submission to Nature (1973), and later breaking confidence, complimented Caroline Tutin and I on our work. Thrilling and reassuring! Later, he wrote many letters of reference for me, at the post-doc stage (1970-73), which made a huge difference in launching a young person’s career. And so it went, for decades, always there. One of the last times I saw him was at my retirement party, where he was characteristically kind, with that ever-present twinkle in his eyes. We shall not see his like again.”

Monique Borgerhoff Mulder

Professor, Department of Anthropology, UC Davis

“Thanks Robert for your consistent support to those of us who were experimenting with applying evolutionary models to human behavior in the mid 1980s. The sight of you arriving at LARG (Storey’s Way) on your bike from Madingley, trousers tied up in bike clips, will never fade. You brought insight and vision to us all as we advanced through academia, a true leader.”

Tim Caro

Professor of Wildlife Biology, University of California at Davis

“Robert was perhaps the key figure in synthesizing the then embryonic field of animal behaviour, and in so doing convinced biologists to take behavioural study seriously. His undergraduate lectures in the Zoology Department at Cambridge helped to sway me that animal behaviour was the world’s most fascinating topic and that I should pursue a career in this field. I am most grateful for that early influence. His mentoring, work ethic and critical thinking were something that we all still aspire to, and he will be fondly remembered by many people.”

Kelly Stewart

“Apart from my parents, Robert Hinde had a bigger hand in shaping my life than anyone else I know. First and foremost, he took a chance on me. I didn’t exactly have a glowing, stellar record from my university years, but I had survived a stint as Dian Fossey’s field assistant in Rwanda and was eager to return to study gorillas. So Robert took me on and taught me how to read and write and think science. He was the reason I was able to follow my dream. He was the most extraordinary mentor.”

Patrick & Lynda McGinnis & Family

“Our love and heartfelt sympathy go out to Joan and all the family.

It will be hard to adjust to not having Robert in our lives. He was always a source of encouragement and understanding. Whenever we lectured or wrote papers, it was Robert for whom we wrote. He was always in our hearts and in our heads. We feel a terrible loss, but his influence will be with us always. He was a wonderful friend and excellent mentor. We feel ourselves fortunate to have known him. We hope we can, in some way, emulate and continue his efforts to make this a better world.”

Lyn McGinnis

“Naturally, Robert’s influence as a mentor will be with us always, but his friendship over the years will be with us also. His letters reflected how deeply he was involved in our lives: how we felt, how we dealt with challenges and changes, what we were thinking about, what was important to us. He shared his feelings and hopes too, for which we are ever grateful, and for the books he sent us to keep us up to date on what was of importance to him.

We have wonderful memories, but the ones I cherish are the moments when (wherever we have lived) I opened the door to see him standing there, and then the joy of having Robert and Joan with us for a few precious days, chatting over breakfast, over dinner, just so wonderful. They are in our hearts forever.”

Pat McGinnis

“I remember meeting Robert for the first time on the shores of Lake Tanganyika at Gombe National Park. He was very encouraging about the research project I wished to pursue on Chimpanzee reproductive behavior. When I became his research student at Cambridge, he went out of his way to provide me with the resources and advice I needed to achieve my goals. He was a constant source of inspiration then and in the many years that have followed. Lyn and I have been very fortunate to have kept in touch with him and to continue to benefit from his wisdom and kindness. We will miss him dearly. Our thoughts and sympathy are with Joan and family.”

Sandy Harcourt

” I wouldn’t be half the scientist I am today, if it were not for Robert. Way more importantly, British ethology would not be half the science it is.

More personally, we surely all have fond memories of the gatherings at Joan and Robert’s house during which our sherry glasses were somehow always full.”

Carol Berman

Professor Emeritus, Department of Anthropology, University of Buffalo.

“‘This splendid man’ is how Caroline Harcourt referred to Robert Hinde in the email message in which I learned about his passing. In my sadness, it struck a note. Robert was indeed splendid, perhaps in more ways than anyone else I have had the privilege to know. I will leave others to recount his groundbreaking empirical and theoretical scholarly contributions to behavioral biology, psychology, the social sciences and moral philosophy. Rather, as a former PhD student of his, I would like to relate the ways in which Robert provided his students with a uniquely engaging and transformative experience at Madingley. I was there during the 1970s during a period that fellow students and I have called Madingley’s ‘Golden Age’, when the lab buzzed with primate field workers coming and going to the Gombe Stream, the Virunga Mountains, Kenya and Cayo Santiago, Puerto Rico. Others worked on complementary projects in the rhesus colony at Madingley or with nursery school children. Our projects were individual for the most part, but our interests revolved around common themes in behavioral ecology and social development that engendered mutual interest, the cross fertilization of ideas, all in a highly cooperative spirit. This mutually supportive, noncompetitive spirit was highly productive, and it in turn engendered a sense of joy, camaraderie and pride in being part of a lab that led such a rapidly growing discipline. As I learned from conversations with PhD students from other labs, this atmosphere was not an accident, nor was it inevitable, or even the norm. It was to a large degree the reflection of that splendid man.

Robert Hinde set the tone at Madingley. He chose students who perhaps by nature were intrinsically more interested in tackling interesting and difficult research questions than in feeding their own egos through science. Nevertheless, he further inspired us to work harder than we ever knew we could, without ever losing our senses of wonder and purpose. Most of all, we felt supported, encouraged and appreciated not only for our work, but also for ourselves. He gave us his full attention as he guided us intellectually, but also as he listened, encouraged, teased and empathized. Moreover, Robert was open to new ideas from his students. Some were related to research, but others concerned personal and societal issues related to gender, politics, social equality and social justice, causes he took to heart, particularly in his later years. His responses to other ideas were particularly endearing to his American students. Although he accepted arguments for some ‘dreadful Americanisms’ such as the use of ‘and/or’, he had a visceral response to the use of split infinitives and to New England autumn leaves, which he considered garish.

Joking aside, I think I can speak for most, if not all of his students by saying that our experiences at Madingley were intellectually transformative, and that Robert’s enormous influence on the field and on his students’ lives on. I personally have not since experienced a period of such intense intellectual growth and engagement. Nor have I forgotten his kindness and his smiling eyes. We owe that splendid man so much, and his memory is very much alive within!”

Frans Plooij

Director, International Research-institute on Infant Studies (IRIS),

“A giant has passed away.

Prof. Robert Hinde was instrumental in getting me to Gombe. As a student I travelled from Amsterdam to Cambridge in 1970 together with my lecturer at the University of Amsterdam Helmut Albrecht, who was about to become the director of the Gombe Stream Research Centre and who introduced me to Robert. My question to Robert was simple and naive: “is it possible for me to go to Gombe and study the chimps?” At the time, I had no research plan, yet. Robert arranged for me to have an interview with Jane Goodall in London two days after we met. As a poor student I did not have enough money for this extended stay and Robert was so kind to let me sleep in his room in St. John’s College. After the interview with Jane and arranging my own grant in the Netherlands with the support of Prof. Gerard Baerends of the University of Groningen, I arrived in Gombe in 1971 together with my wife Hetty van de Rijt. We studied the behavioural development of the chimpanzee infants and the mother-infant interaction. Again, towards the end of our stay in Gombe, it was Robert who invited us to come to the Sub-Department of Animal Behaviour in Madingley, Cambridge, to analyse our data and write our Ph.D. theses. While I was to defend my thesis at the University of Groningen with Gerard Baerends as my ‘promotor’ and Robert as my ‘co-referent’, Robert was instrumental again in getting my wife Hetty accepted in the department of Physical Anthropology of the University of Cambridge as a Ph.D. student. She defended her Ph.D. thesis with Robert as her internal examiner and John Bowlby as her external examiner.

Robert Hinde was kind and caring. With his critical mind, for young students he could also be downright intimidating. Looking back, I realise that being exposed to such a critical, sharp mind was the ideal way to grow intellectually, and grow fast. It was Robert’s way of caring for our scientific development.

A giant has passed away.”

Magdalena Janus

“I hesitated to contribute to this webpage because I cannot write a tribute to Robert Hinde without making it intensely personal. In everybody’s life, there are people that influenced or nudged them. I have had several of those too. And then, there are people whose influence makes you who you are. That was Robert’s impact on my life. If, about thirty years ago, Professor Robert Hinde of Cambridge University, had not chosen to see something worth supporting in a 23-year-old diffident woman who had a Master’s in zoology from the best Polish university, but no official status or occupation in Cambridge beyond that of a wife of a post-doc, I would not be writing this post, I would not be where I am now.

Going back all these years, I am now thinking, that maybe it was actually Jerome K. Jerome who helped?… In early October, barely a month after we arrived in Cambridge, Robert and Joan invited us for a Sunday lunch. There were others there as well. I followed the conversation as well as I could, and I think maybe even contributed a little? After lunch, Robert took the few guests for a walk along the fields, and for some reason an issue of a “handmaid’s knee” came up. “I’d better explain it”, I think he said, for our behalf. “I know,” I said, “it’s in ‘Three Men and a Boat’”. “And of course, you read it?” he laughed. “Of course” I said.

Robert was not the first or only professor in Madingley who knew that I was desperately hoping for some chance to be involved in research. He was, however, the first to do something about it. There used to be a volunteer assisting in observing monkeys in Madingley, but she left. Robert said he would find out whether they still needed someone.

Soon after, I was told to show up in Madingley. My experience with animals was limited to beetles, but to my surprise I took to primatology like a fish to water. This was what I was born to do. When a few months later, I raised enough courage to think that maybe I could actually study them for a PhD, I went to Robert and explained my idea. “Why do you want to study it?” he asked. “Because I think it is interesting….” was my naïve answer. “You know, he said conversationally, saying that something is interesting is like a kiss of death. Anything can be interesting. Why do you really want to study it?…” To this day, I avoid saying that something is interesting.

Robert Hinde was not a supervisor of my PhD – by then he was not involved in primatology anymore, but he was the Benefactor whose backing got me my studentship, and mentor – and as years passed became more of a friend and a stalwart supporter – someone always in my corner when I needed him. That continued through the years. For some reason, he believed in me, and used that belief to help me. I thanked him many times. But probably not enough. I like to think that his influence makes me a better scientist, a better teacher, and a better person, in big and small things alike. That is a difficult hypothesis to prove. What I do know, what all of us who came into Robert’s orbit know – is that we are so much richer for having been so fortunate to know him. ”

Anthony Collins

Gombe Stream Research Centre

Gombe has many reasons to remember Robert Hinde, mainly because he set a high standard for studying wild primates. He showed how, by stringently documenting social interactions you can characterise relationships, from which you can identify their social structure. He also introduced us to checksheets, which still live on: every day at Gombe between two and ten Tanzanians are out in the forest recording behaviour on checksheets whose lineage can be traced back directly to his teachings here.

He also brought great clarity of thought on primate social life: how to tease-out the dominance relationships between pairs, whether hierarchical or not, and how to separate dominance from leadership and roles: these insights enriched our observations in the field.

He was also an excellent teacher, his honours course in animal behaviour was a gold-standard, and ushered many clear-thinking ethologists into the world.

And at postgraduate level he was a famously stern supervisor: but by so being he purified the quality of the research, and likewise the quality of the people: it was said that when people (like me) came asking for an opening in animal behaviour, he would do his best to talk them out of it: but if they were still there at the end, he was singular for the extent to which he would listen and concern himself with each one. Just as he thought clearly in his science, so he was prepared to think clearly about you !

He also assisted Gombe greatly at the time four western researchers were kidnapped by the forces of Laurent Kabila from DRC, then Zaire. None of these four was his students, but two of his (Richard Barnes and Juliet Oliver) were near misses, and he was immensely supportive of the whole Gombe group at that time and after they came home.

So for many of us individually, and for Gombe as a whole, his legacy is great, and I am sure we will carry him on with us, for the great part he has played in our lives. ”

Kathlyn (Rasmussen) Robbins

Research Scientist, National Institutes of Health, 1987-2014

I was Robert Hinde’s graduate student from 1976 to 1980. In many ways I think it’s as difficult to speak objectively about a great teacher or mentor as it is to speak about a parent; certainly his influence on me has been as pervasive.

Robert had one of the sharpest and most logical minds of anyone I’ve ever known. He held everyone to his standard of scientific rigor and could be merciless in the face of what he perceived as sloppy thinking or arrogance unsupported by facts. As a scientist, he was internationally renowned for his incisive analyses and encyclopedic knowledge. When I first met him he was recognized for his avian research, but he’d also written a definitive textbook on animal behavior that was the standard in the field for many years and he’d collaborated with psychiatrist John Bowlby on research and theorizing that would become the basis for Attachment Theory. Rather than worry about reinventing the wheel, he was fearless in his approach to fields other than his own, whether those were child development, relationships or ethics. He simply went into the literature, stripped away the jargon, examined the evidence, and extracted the useful from what remained. From comments he made, I suspect that he felt he was more of a synthesizer than a creator– -but what a synthesizer! His Curriculum Vitae listed his many books and concluded with the simple statement “and published articles.”

When I returned to Cambridge after completing my thesis research in Tanzania, I was one of a number of Robert’s students there at the time that had experienced difficult and sometimes dangerous field conditions. Some of us had seen kidnapping by guerilla forces, some had encountered danger from poachers, some of us had experienced daily fear of animal attacks while we collected data on foot in national parks. And probably all of us had some lingering effects of social isolation that made us feel out of step with the civilized, normal world. Robert observed this and with his characteristic decisiveness vowed to do something about it. With input from his graduate students he put together a questionnaire to dissect out those aspects of fieldwork that were most stressful, and published the results with an eye to helping other students avoid or at least anticipate potential problems.

Very early on I became aware of how unusual Robert’s mentoring style was. Graduate students from other departments at Cambridge complained how unresponsive their graduate supervisors were and despaired of finishing their theses in the face of almost no feedback from them. In contrast, Robert would walk out to the graduate huts in the Madingley compound to find a student who hadn’t communicated with him recently, and invite them in to his office to talk about how their analysis or writing was going. If a student went into his office with a problem Robert either would stop what he was doing and attend to it immediately, or ask the student to come back later that day. I was in awe of his ability to shift his focus away from something he was working on and then back again. When we submitted a chapter to him to read, we would get it back not weeks later but within a few days– -usually covered in red ink and always accompanied by copious notes. Beyond that practical level of support, Robert understood the emotional loneliness, frustration and often confusion that accompany months and years of data analysis and thesis writing. I will always remember him saying to me “Kathy, there is order in Nature.”

Perhaps one of the most valuable lessons Robert passed on to his students was his extraordinary eclecticism. His intellectual curiosity made him very open to new ideas (subject, of course, to his logical examination), and he actively encouraged his students to seek out information in other fields. When I was puzzled about my female baboons’ behavior during different phases of their cycles, Robert sent me to see someone in the Anatomy department who specialized in hormonal influences on behavior.

Similarly, an odd result in my subjects’ activity budgets prompted a visit to the Nutrition department. Science often advances with the use of analogies, and Robert taught us to cultivate that kind of wide-ranging, out-of- the-box thinking. It is no accident that his students are represented in so many different fields: zoology, anthropology, psychology, psychiatry, child development and others.

Roberts’ concern for his students extended far beyond their time at Madingley, and his sense of responsibility and efforts to assist them likewise exceeded those of a typical supervisor. He worried particularly about his American students returning to the States, because as he put it, “Science is run like a business there”. I’m not alone in having maintained contact with Robert for many years after leaving Cambridge. There was the usual Christmas card level of updating, but I also wrote to him when I encountered an especially interesting new idea or a thorny intellectual problem. He would always respond with comments and often very helpful insights and references. Face to face visits were rare, but if he was travelling for a conference and happened to be in the area he would always try to make time to meet.

Robert Hinde set a benchmark for scientific rigor that became an integral part of my life as a scientist,and which has influenced almost every part of my approach to life in general. I will miss his presence.